Photos: Rachel Nadeau

For decades, Mound resident C. Ray Frigard has made a living as a largely self-taught designer and inventor and, more recently, an author.

What is an autodidact? Simply defined, it’s a person who is self-taught.

Mound resident C. Ray Frigard could be considered a classic autodidact. For decades, he’s made a living as a largely self-taught designer and inventor and, more recently, an author of both nonfiction and fiction books.

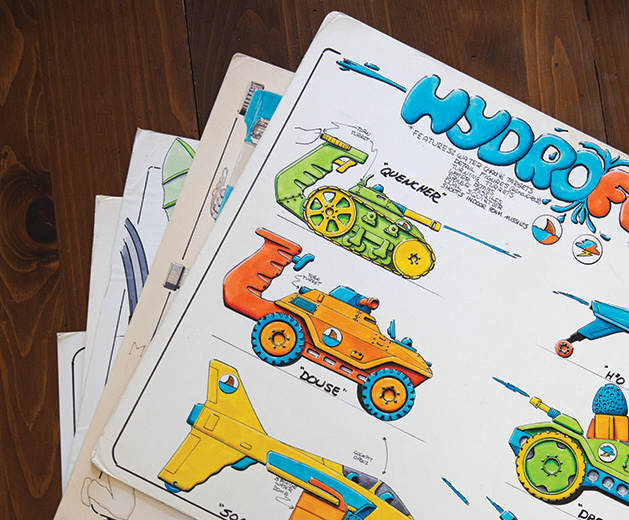

Originally from the Detroit area, Frigard moved to the Twin Cities in 1971, to work as a sculptor for Tonka Toys. Frigard got his first design job as a sculptor at Ford Motors, after earning a bachelor’s degree in social sciences from Michigan State. “I made a model in my apartment, and got a job. They called us clay modelers. Over the years he’s worked on Thunderbird interiors, BMWs and Mini Coopers.

A model car made by C. Ray Frigard

In the ’80s he “took a detour” into his own design, sculpture and inventing business, under the Frigard Design shingle. (The inventing business is TreeBones, Inc.). His most recent design gig was a decade spent with Polaris, establishing and building a clay sculpting department; now the 77-year old spends most of his time on his writing.

As inventor and owner of TreeBones, Inc., he is named on a variety of patents: Rollerblades, cameras, recreational vehicles, computers, sailboats and toys. As a toy and game designer he has licensed concepts with many of the leading toy companies, most notably Crossbows and Catapults, with Lakeside Games.

Where did all his creativity come from? Frigard remembers growing up with a father who was “pretty creative,” and he assembled model kits as a kid. But he never had any art training, up to the time he began working as a car modeler.

Figuring out the source of his creativity is what’s driven him to write two books on the creative process (FunThink and Arthink, self-published on Amazon), and teach kids how to be creative. “In most academic classes, like math and science, we learn there is one correct answer. But to come up with something original, you have to create something that isn’t there. That’s been my passion for 15 years, trying to educate kids.”

Frigard likes to pass on what he has learned, teaching a creative problem-solving class for kindergarten through eighth grade students at Our Savior Lutheran Church School in Excelsior.

Through a local friend who made cast figures, he also landed a gig sculpting figures for Disney, Muppet-master Jim Henson, and Garfield creator Jim Davis.

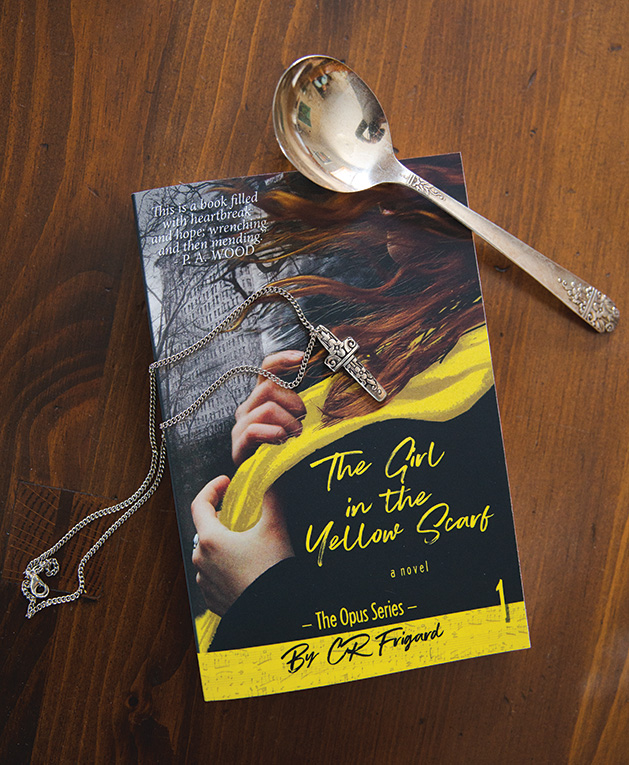

Frigard says his foray into fiction-writing was inspired “completely out of the blue” by a couple he observed while heading to a movie at Eden Prairie Center. His observations led to his three Opus series books.

“I spend a lot of time observing people, especially since that happened. I find myself taking mental notes about how people treat each other, nuances of their speech. When you write fiction, people need to believe what you are saying, so you want to use truth. It started as a short story, but I followed it, like bread crumbs.”

He set his books in 1980s New York City, where he spent a lot of time going to toy fairs. The protagonist is struggling NYC pianist and composer Mike Monroe, who meets a homeless young woman who is in poor health, but is also a talented artist and singer. She becomes his muse; a song he writes about her, “The Girl In the Yellow Scarf,” leads to record contracts and a hit Broadway musical. His initial idea turned into a trilogy; the second and third novels in the series are The Piano Man and The Opus Cafe -Where the Lost Are Found.

All five of his books are available on amazon.com and in about a dozen bookstores around the Twin Cities. On his website, he suggests that book-buyers go to their local indie stores first, “to help keep them alive.” At readings, he’s developed a discussion format in which he describes his approach to plot and character development, and how the books evolved.

And, of course, he’s always open to the next creative idea that might—probably will—mysteriously appear. His advice for others: “Whether it’s an idea for a book or whatever, get it down on paper first, so you don’t lose the essence of what the inspiration was. If you try to edit too soon, you might go ‘down the rabbit hole’ and lose the flow of inspiration.”